Incense Ceremony for Spring Equinox 2018

Ceremonies are a combination of the meticulously planned steps and procedures, and the chemistry or effect this process has with the people attending. I believe it's the latter who really sets the tone and brings out the essence or spirit of the ceremony and its intent.

Yesterday I conducted an incense ceremony to celebrate the arrival of spring. Things did not go quite as planned in terms of attendance. So I ended up actually having two ceremonies: A prep one with Miss T, my Sister-in-law, 3 nephews, and baby niece, in which we had lots of laughs trying not to blow off the ashes in which the charcoal is buried.

We started off by "warming up" our noses with a few simple ingredients (patchouli, vetiver, sandalwood, ambrette seeds; then we went through all the six ouds I have in my collection and finished off with some special neriko that was gifted to me by incense friends). I spent most of the night before in a sweat lodge and felt it was really important, after all the cleansing and sweating and burning off negativity and challenges - to invite sweetness into the spring.

Here are some brief notes from the ouds we've experienced that afternoon:

Hakusi (spicy/hot incense from Vietnam): Musky, animalic, woody, changes a lot throughout burning. Perhaps can be classified as Manaka.

Ogurayama (sweet incense from Vietnam): Sweet indeed, dreamy and rich. My nephew called out with a big smile: "It's a Garden of Eden for candy".

Tsukigase (Vietnamese raw aloeswood): Weak and a little hot/peppery.

Assam Aud (gift from Persephenie): Camphoreous, hot-spicy, yet at the same time dry, yet sweet; or perhaps cool-sweet. Smells a lot like Japanese body incense.

Papua Shimuzu (Gift from Ensar Oud):Desert-dry at first, woody, bitter, acrid and perhaps a little sour to. A little like sandalwood. Perhaps can be classified as Rakoku.

The evening ceremony I actually had to cancel because of too many last minutes cancellations, and still there was someone who did not register at all, and actually was the only one who showed up (!). I forgot those things tend to happen, and feel bad that those who intended to come missed out. We had an impromptu ceremony that was not quite as I planned, but still fantastic. We burned what I felt intuitively was the right materials for her, and we had a pace that was responsive to her experience, in terms of toning down or up the intensity and switching materials when she had an overwhelming reaction to something. We burnt patchouli, vetiver, sandalwood and one type of oud (Papua Shimuzu).

Last but not least, here are the details of what was my intended ceremony. Koh-doh ceremonies are at an interesting cross between oud-binge, poetry reading, calligraphy and olfactory identification games. In that spirit, I planned out an event to celebrate Hanami's anniversary with the poem that inspired it. This poem and the associations I have with it dictated which materials we were going to burn, each symbolizing a particular aspect of the poem:

Metro Station: Vetiver rootlets, for their dusty, cool-woody and somewhat metallic scent

Faces in the Crowd: Costus root, for its oily scalp smell like many people on a train and the forced intimacy that happens in such crowded areas.

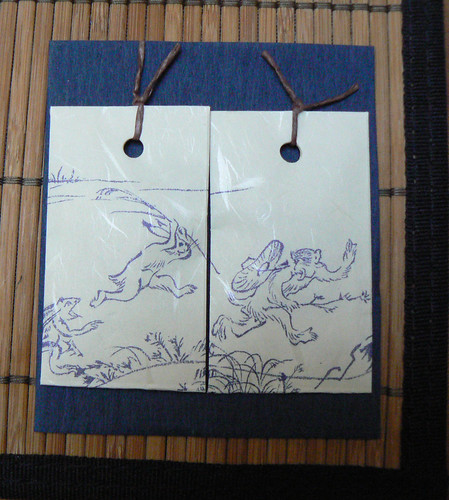

Sakura Blossoms: Either a Rose Nerikoh (by Yuko Fukami), cherry blossom incense stick, or ume blossom incense pellets that are shaped as actual flowers (see above photo).

Wet, black bough: Oud of some sort - preferably one with more "watery" or "cool" feel to it, rather than the hot, bitter, sweet ones, etc. For example: Assam agar wood.