There is a little confusion around the name "Za'atar" and what exactly does it refer to: A condiment? A spice mix? An herb? And if so - which herb exactly - Hyssop? Thyme? Oregano? Marjoram?

The truth is that za'atar is an Arabic word used interchangeably for a number of wild herbs that grow wild in the Mediterranean region, and all contain

thymol and

carvacrol. Hence their similar sharp and warm aroma, bitter taste and spicy, almost hot "bite". They also share similar medicinal properties, most of them used in folk medicine for most digestive ailments and respiratory complaints. The mixture known to us as "Za'atar" is in fact a misnomer. Za'atar is originally the name of the plant now classified as

Origanum syriacum, but in Arabic it is loosely applied to several other related wild and not so wild herbs.

The name for the condiment is in fact "doukka" (pronounced often as "Do-ak" with a very throaty "K" that almost sounds like an "A" so in reality the word sounds more like "Do-ah"). In Arabic this means "to grind". Each region in the Arab world has its own "Doukka", which is either sprinkled on food, or more commonly covered in olive oil to which the traditional regional bread is dipped. For example - Egypt has a complex nut-based doukka with toasted hazelnuts or walnuts, to which toasted or untoasted spices such as cumin, coriander seeds, green peppercorns and sweet fennel have been added.

In the Levant "doukka" happens to be made primarily of a mixture of thymol-containing herbs, with "The" Za'atar (

Origanum syriacum) being the star of the show. Lesser amounts of other herbs, will be added - the most important of which are "Za'atar Farsi" (winter savory), Israeli Thyme (

Corydothymus capitatus), Zuta זוטה לבנה (

Micromeria fruiticosa barbata), a delicate wild white mint known in English as White-Leaved Savory (which does not even belong to the savory genus, but to micromeria because of its tiny leaves). Common oregano (

Origanum vulgare) makes a good addition, albeit cannot substitute for the real Za'atar or Syrian oregano if you actually know the real deal. Likewise, marjoram and thyme can also make a good addition but not be at the centre. Even though their profiles are similar - there are some nuances that will be lost if using only the garden variety oreganos and thymes and none of the wild stuff.

Many other things can be added to the mix, the most important being

sumac berries (

Rhus coriaria) for their wonderful salty-sour flavour, and toasted sesame seeds for their pop-in-the-mouth nuttiness. But you'll also find spices sometimes, including more obscure ones such as

butum (بطم) - toasted terebinth fruits (

Pistachia palestina), which are really like tiny pistachios with the outer red peel intact. I've got a few of those drying right now, because I've never seen them in any market before and I'm very curious how they taste as a spice.

The following are several authentic Za'atar recipes I've collected - and of course you are welcome to browse google's universe of shared recipes, but be cautious of a few things if you want to make an authentic za'atar:

1) Use actual Origanum syriacum even if a generic "oregano" is called for

2) Do not by any stretch of the imagination use "fresh" leaves. They must be dried first. And only then will you grind them up with the rest of the ingredients. This is a dried herb and spice mix. Not a fresh herb concoction.

3) Usage of salt, although found in many recipes, seems very superfluous to me, unless you are not using sumac berries. These have a unique taste - equally salty and tangy. The whole point of using them is so you do not need to use salt. Likewise, using citric acid is a way to fake the sumac effect. Which I'm not quit sure why would anyone do that aside from laziness. Sumac berries are difficult to grind manually (or even in a coffee grinder) - but you can find ground sumac easily in many spice shops and markets.

When shopping for pre-made spice mixes, or any ground spices for that matter, the main culprit is adulteration and using old raw material that are "dressed up" as authentic. It's hard to teach someone who've never tasted or smelled za'atar what to look for, but some things are a telling sign. For example: if you don't see the dark maroon red and still taste salt or tanginess, it is probably from salt and citrus acid, and not from the (missing) red sumac berries. Secondly, another visual sign - za'atar leaves are rather grey in colour when dried, so any other colour you see (olive green) is either food colouring or a combination of other types of "za'atar" herbs (i.e.: thyme, za'atar farsi, etc.). Best sign is by taste - if it taste like dust (and looks like dust) it's either too old or just a fake.

I suggest you start with the most basic three ingredients, and then play with the proportions and adding other herbs and/or spices. You can even start with equal amount of za'atar leaves, sumac and sesame and adjust to taste.

Safta Ada's Za'atar Recipe This is my mom's handmade recipe that she would make from wild harvested za'atar (before it was illegal to pick any) and would even send it to Vancouver so I can enjoy a taste of home.

1 cup dried za'atar leaves, coarsely crushed between your palms, or pounded with mortar and pestle to a finer powder4 Tbs ground sumac berries (I suggest you purchase them pre-ground, otherwise their seeds can break your teeth!)2 Tbs toasted brown sesame seeds, wholeMay Bsisu wrote an excellent book,

The Arab Table, which I highly recommend, and it includes a unique Palestinian style of za'atar that includes caraway:

10oz oregano (I assume she means za'atar)5oz thyme3 Tbs sumac, ground1/4 cup toasted sesame seeds2-1/2 Tbs coarse salt1/2 tsp allspice, ground1/4 tsp caraway seeds, ground Easy Lebanese Recipes provides a "Traditional Rich Recipe" for za'atar that I'm compelled to try, with dried za'atar, roasted sesame, sumac, marjoram, coriander, cumin, cinnamon, fennel, aniseed and salt.

Mamma's Lebanese Kitchen recipe contains thyme, marjoram, sumac, sesame, cumin, coriander, fennel, cinnamon and salt.

How to consume za'atar?Use your za'atar mixed with olive oil as a dip for bread, on top of labneh (strained yoghurt cheese) or as a substitute for butter under any other soft or hard cheese, avocado, etc.

It's also a nice addition to salads, and for baking fish or poultry. I also like to add it to chickpeas that I fry whole in olive oil, after they've been cooked and drained.

Fresh za'atar leaves come in late winter and can be enjoyed all through spring, and can be fried in olive oil much like tender sage leaves and become this wonderful crispy topping for fresh bread, pasta, roasted vegetables, etc. Also, they can be used as they are in salads (May Bsisu has a recipe for fresh oregano salad in that book as well), with lots of onion and tomatoe. The Druze use it to season the dough or the fillings for various savoury pastries, such as sambusak (a flatbread that is folded in half to conceal a thin layer of highly seasoned stuffing, and baked in the

tabun) and

fatayer (little dough pockets filled with cheese), and the dried whole leaves can be used much like oregano in meat and pasta sauces, in soups, stews, breads, etc.

Now, let's explore the Za'atar "group" of plants:

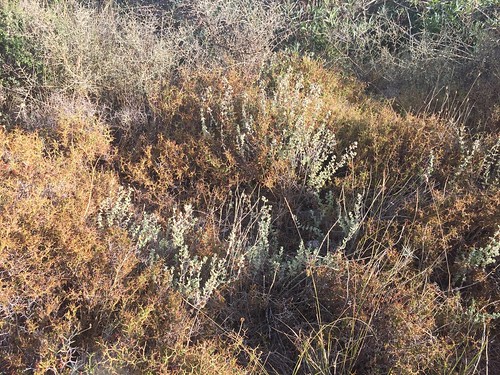

Ezov (the Hebrew word for the Biblical Hyssop - not the European

Hyssopus officials which is also a medicinal plant, and produces a rather toxic essential oil), which is now classified as an oregano,

Origanum syriacum (formerly Majorana syriaca). Like many of the other aromatic plants from the Lamiaceae family, za'atar has a winter and spring foliage and a summer foliage, which is smaller in order to preserve water and survive the long arid season. I suspect the essential oils also aid with the survival of these plants in such harsh conditions - because whenever they are grown in regions where the water is more abundant (British Columbia, for example) - their flavour is largely lacking. What you see above is the luscious winter "look", which features soft and larger leaves, and their colour is much greener, and therefore more similar to the common oregano (

Origanum vulgare).

Za'atar Farsi (meaning Persian Za'atar), or as it is called in Hebrew צתרה ורודה - Tzatra Vruda (Pink Tzatra) which really is winter or mountain savory (

Satureja montana). Its long needle-like leaves have a sharp, spicy taste. When we were growing up my mom would spice the egg for French Toast with them and make them literally savoury.

Mediterranean Thyme (

Thymbra spicata), in Hebrew צתרנית משובלת Tzatranit Meshubelet is also called in Arabic "Za'atar farsi", and has a very similar leaf shape (only a bit longer, narrower and softer) and almost identical odour and aroma profile. It has flowers that look a bit more like chaffs of wheat (not unlike those of

Lavandula dentata, and is even more rare to find than Satureja montana.

Israeli Thyme (

Corydothymus capitatis / Thymus capitatus / Thymbra capitata) or in Hebrew Koranit Mekurkefet קורנית מקורקפת is also known by many other names - Israeli oreganum (oil), Cretan thyme, Corido thyme, Headed savory, Thyme of the Ancient, Conehead thyme and most commonly - Spanish Oregano (even though it is not classified as "origanum"). This oil is what is often sold as "oregano oil", by the way. This is now a rare plant that in our area grows only along the rocky seashores of the North Coast leading to Lebanon. The leaves are tiny and sharp, like a miniature version of the Pink Tzatra, but they grow more dense and close together to form clusters around the tip of the branches. The branches are woody-looking almost like bonsai trees that crawl all over the rocks - and the flowers tiny and purplish-pink. The aroma is clean and maybe a little more simple than that of za'atar, but also the taste is much more sharp and phenolic.