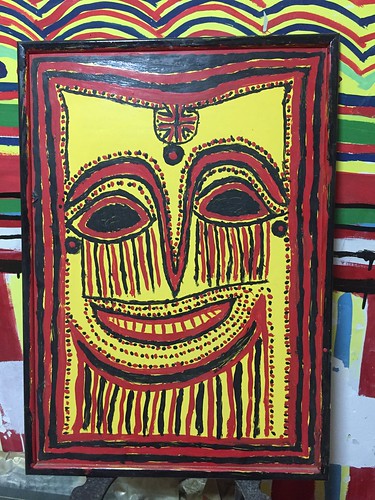

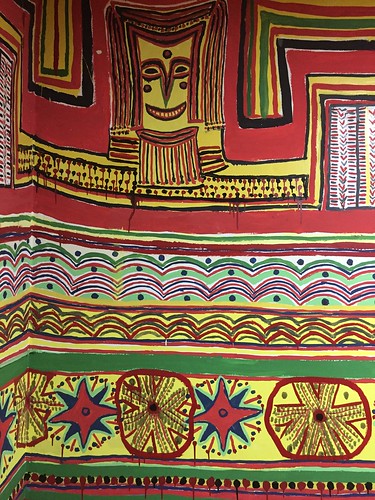

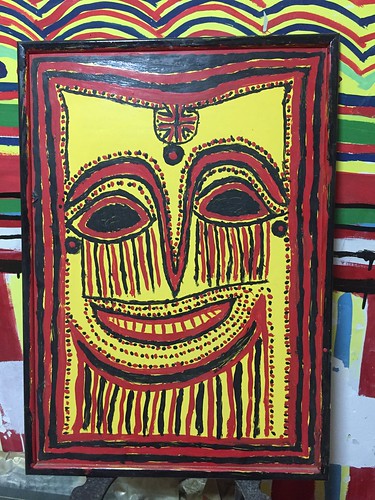

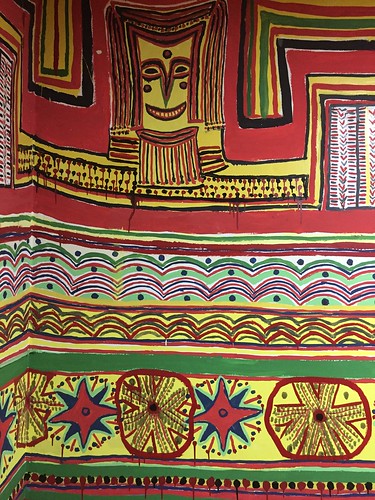

In the edge of the sleepy border town of Shlomi, there is a run-down neighbourhood of subsidized housing whose appearances are as yawn inducing as ever. You pass by a synagogue down an abandoned alley, courtyards with neglected gardens, and walk a few stapes up the mouldy staircases, and then there is a gate to an otherworldly temple. Even before the door is opened for you, you know you're stepping into a different time-space zone. It is decorated with intricate designs, resembling an African weaving patterns.

The moment you step inside, the colours shout at you from all directions. Very striking earthy and almost primary colours, reminiscent of African art and perhaps also with some Mexican association (if it weren't for the very sparse use of azure colours). There is also an overpowering scent of highly-perfumed floor cleaner. There is no place for the eye to rest or think of anything else but what the artist intended to create here. A magnetic energy both suffocates you and transports you into the inner corridors and innermost secret chambers of her life, and death.

The foyer is tiny, and packed with portraits and collages of the artists superimposed over newspaper clippings. Before you realize where you are, you're already in the kitchen, of which the only homey remnants are the aluminum pots still stashed away in the cabinets. But in this context they seem more like witches cauldrons than anything else, and it's hard to imagine any sustenance cooked within these spirited walls. Behind it is a service balcony with broomsticks and buckets and other cleaning affair, also looking like they carry much more magical meaning than their humble appearance. It seems like not even a good idea to step closer - like the Sorcerer's Apprentice, at any moment these object may start walking towards you and drown you with bucket-water all on their own. The broomstick is also painted with zebra-like stripes, and all the pipes running through this balcony are meticulously decorated, to conceal any distracting parts of reality from the eyes of the beholder.

The other rooms are just as haunting, an disturbingly intimate - with beds laid with the same blankets and bedsheets of the artist who dwelled her, and with the artist's personal belonging in the painted closet: antique face powder, with an unrealistic peach colour of no real skin... Crusted-blood-red nail polish, hand creams, medications, and a quarter-liter Eau de Cologne that smells nothing fresh or cologne-like, but rather like a deep, rich ambreine perfume, in the vein of Shalimar: some bright bergamot drowned in a syrupy concoction redolent of vanilla, castoreum and patchouli. The legendary perfume that Afia's children remember her by is probably sitting right in front of me.

This is The Paineted House of the late artist Afia Zekharya. You don't need to know her life story to appreciate the power of her art and the magic of this space where she lived and ultimately died. But it sure helps to understand why she did what she did: spent the last 15 years of her life covering everything inside this apartment with art. Also, similarly to other female artist that focus on their internal storytelling, and although her art is immensely biographic, it is more figurative and symbolic, and less elaborate than Frida Kahlo for example, whose art also portrays the deep suffering - although infused with joy - she experienced in life.

There is more unknown about Afia's life story than there is know, party because she spoke only Arabic, and therefore hasn't communicated much with her neihbours. But also because her family keeps its privacy, and does not like to be interviews about here. Whether it is to protect her memory or because they are media shy, we will never know. But we do know she was born in Southern Yemen, got married off at a young age (probably 10), and has immigrated to Israel with her husband, a traditional Yemeni jewellery artist (if you haven't seen Yemeni silver jewellery - it is very ornate, and requires much skill), and their six children (although according to what I've heard she's given birth 15 times - so most of the children did not survive). They were first settled in a big Arabic house in the abandoned village of

Al-Bassa, whose inhabitants fled during the War of Independence/AKA The Naqba in 1948. The village was mostly ruined and on top of it was built the moshav Betzet, and parts of the industrialized section of the new Israeli border town of Shlomi.

It was a big house with garden and yard and Afia had dedicated her life to raising her children, cooking traditional Yemeni food in a taboon (a specialty clay wood stove for baking flatbreads) that was built in the house - a lifestyle I imagine was still somewhat familiar to what she had in Yemen, despite being displaced in a new foreign country. But before each day has began, she would take great care adorning herself: painting her fingernails with nail polish, wearing Yemeni regalia and jewellery and dousing herself with her signature perfume - an Oriental concoction that is forever engrained in her children's and grandchildren's memory. Perhaps this was her only pathway for self-expression, because Afia was forbidden by her husband to pursue her true passion for painting - something that according to a rare interview from 1994, she was very good at and was even recognized for while living in Yemen. According to her story, she was so gifted and her art so loved that she was especially commissioned to paint a king's palace in her youth.

But sometime in her old age of 80, after all her children left home, and her husband already among the dead - Afia was displaced again. This time because the town of Shlomi needed the land where she lived to expand the industrial compounds. Without knowing the language, she was signing a lease that robbed her of her house, and instead was provided with a claustrophobic rental space in the Amidar neighbourhood of Shlomi. No garden, no chickens, no taboon to bake her bread. Instead of using the sun balcony to keep contact with the world, Afia shut herself in and in secret, with cheap paint, began telling her story that was locked inside her all these years, on every surface of the house. Including all the walls, the frosted-glass window panels of the sun-balcony, the screens that keep away mosquitoes, the cupboards, closets and even the toilet bowl. Then the floors, (all the parts that were not covered by carpets, so now that the carpets were removed, you can see some bare floor). And finally, despite her short height, painted the ceiling. To overcome her height obstacle, she placed a chair atop a table and methodically decorated the entire ceiling in each and every room in the apartment. She was almost done painting the last square meter of the ceiling when she fell and injured herself so badly she had to be hospitalized.

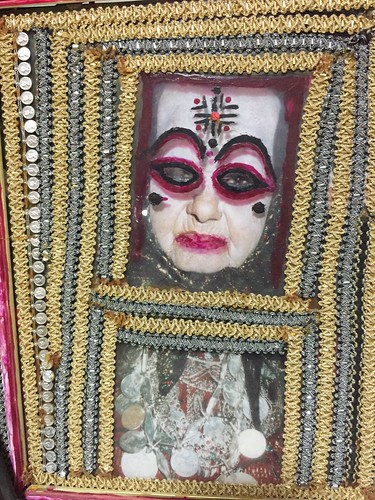

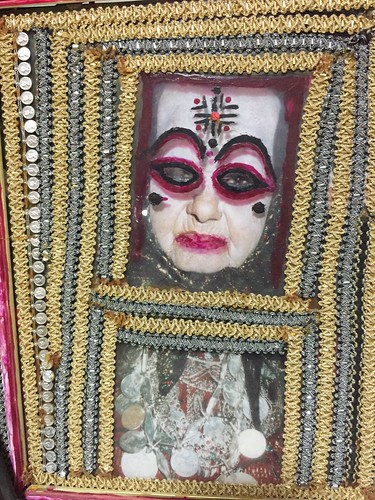

But that injury did not stop her creativity. She now stocked up on multiple dolls from the souk, created Yemeni regalia to cover their bare plastic skin, and painted their faces with traditional Yemeni -style "makeup" - adorning their eyes with blue and black frames, painting their lips a bright red and adding henna-like decorations for their skull-like yellow-painted faces. Like the pattern on the walls, all the faces replicate each other, and all replicate Afia's face, which she also painted, reigning on her kingdom of painted dolls. As if frozen in time in their childhood, the part in life which Afia was never really able to live to its fullest. They're stuck in that moment in time, the night of there Henna ceremony, their eyebrows and forehead smeared with Z'bad - a seductive solid perfume made of civet paste, camphor and spices.

The dolls look all alike: their seamless baby-plastic complexion suffocated by cakey makeup and weighed down by heavy metal jewellery and ornate ceremonial Yemeni-wedding embroidery. Their once innocent appearance now seems menacing. Frozen on the eve of their wedding night, like a serial-killer's victims - or perhaps like a murderess themselves.

This art and the house struck a chord with me on many levels. First of all, because Afia Zkharya is also a

Fringe Artist like

my daughter Tamya (an autistic artist that paints and draws purely out of her own need to express herself, and less so from a need of an audience or recognition). My daughter's innocent portraits seem violet at times - wide-smiling "happy" girls exposing sharp teeth and claw-like nails, surrounded by dense patterns and many colours.

Secondly, on a more personal or emotional level, being a woman and having experienced the blurring of my identity (being raised by a stepfather of Moroccan descent who hated anything to do with my European heritage, he insisted on silencing of my voice and criticizing me whenever I was singing German Lieder or Italian opera), and the general oppression of my art and creativity while growing up - especially confusing when on the surface it was nurtured and encouraged, and I was constantly praised for my "talents". Something that I believe a lot of women can relate to. As women, we are often not allowed to show the full spectrum of our emotions, not even through a socially acceptable form of art. And this is especially apparent in more traditional patriarchal societies and those still strongly dominated by that.

Last but not least, on a more political level, being an Israeli all those oppressive events, such as wars and violence, and especially violence agains minority groups and women from those groups is deeply disturbing and affects me even if I wasn't an Arab-Jew or an Arab-Palestinian thrown out of my home, or

having my children stollen (which happened to many Jewish women from Yemen, the Balkans and other Arab-Speaking countries) on the pretence that they were still-born. This is an affair that is only recently being acknowledged by the Israeli government - being denied as being an urban myth even though we as a collective all knew and believed the victims all along, a story that kept being told and there was no other way. This kind of pain is not something that no matter how much you try to - it cannot be erased or denied. The truth comes out because it is part of people's lives who live among us, even if it doesn't affect us directly. And this is also true for the

Sixties Scoop in Canada, which is a too-obvious comparison, and has bled through all level of society, whether if we like to acknowledge it or not. Jut like a war, you can't have a whole generation scarred and lives displaced and shuttered this way without having a multi-generational effect on all of society.

The fact that her art is recognized, and the Painted Palace saved from erasure, just as Afia insisted on expressing herself despite all odds, and being rented to another family is a consolation. Just like the artist has and preserved her language and her name (Israel's melting pots of the 1950s and beyond was very aggressive about morphing everyone into "Israelis" and not allowing preserving their identity and culture from abroad - beginning by forcing people to forget their mother's tongue, and change their names into Hebrew names. For example, Afia, which means Health in Arabic was "Hebrewsized" into "Ofra" (which means a baby deer), Now the art and culture division of the town of Shlomi is fundraising for preserving the house so that many more generations can experience this magical place and be touched by Afia's story and the suffering she's endured. Like Dia de los Muertos, this creation feels more like a commune with the dead. Next time I go there I want to bring a Yemeni soup as an offering, and give Afia's doll one of my cherished jars of Z'bad I received as a gift from my friend Dan, to refresh her painted face and perfume all her self-portraits.