The topic of what makes a fragrance masculine comes up very often in the natural perfumery forum I belong to: which notes re “masculine”? How to construct a “masculine” fragrance? Can flowers be used in masculine fragrances?

Today being father’s day, I figured I’ll take advantage of the situation and talk about the entire concept of masculine scents. Not so much from the wearer’s point of view, but from that of the perfumer, when designing a scent in such a way that it will appeal to men and will not scare them off chased by flowers…

So let’s break a few myths on the topic:

Myth: no. 1: “If a man will wear a perfume for woman he will smell feminine”.

Reality: A perfumer who thinks that way is forgetting the last yet most important component that is added to a perfume, and on which the perfumer has no control over: the wearer’s skin odour. Each skin has a completely different scent, affected by the diet and metaolism of the person for one thing – and their own gender’s pheromonal makeup. Men and women do not have the same scent. Therefore, what truly makes a fragrance “masculine” or “feminine” smelling is the person who is wearing it.

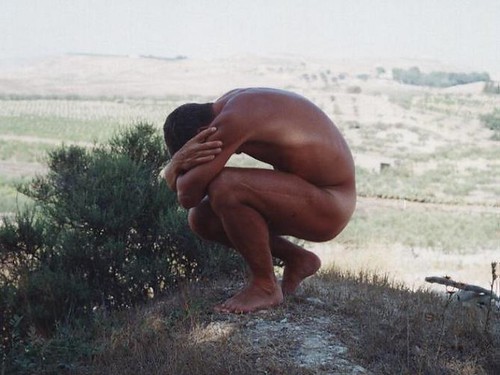

Naturally, men have a body odour that is more musky and sharp, and women have a body odour that is more ambery and soft. If the perfumer will try to compare these into specific notes, I’d say that the closest notes to a man’s body odour might combine notes such as sandalwood, costus, cumin, hay, patchouli, vetiver, oakmoss and ambrette. A woman’s body odour can be best described olfactorily by notes such as labdanum, vanilla, benzoin and honey absolute (with labdanum being the closest I suppose).

So, don’t forget the base upon which the perfume will be worn, and how this surface smells like. It will all boil down to this…

Myth no. 2: “floral notes are feminine and are best avoided when composing a masculine fragrance”.

Reality: Attributing floral notes (or any notes, for that matter), to one gender or another is completely culturally based and once presented to a different culture, may completely lose its meaning. I like to bring the examples of how fond the Arab men were of roses, and how jasmine is traditionally considered a masculine perfume in India. If Arab men felt comfortable enough with their masculinity when wearing soft and voluptuous roses, I can’t see why avoiding this note (or any other floral note, for that matter), in fragrances designed to be worn by a man.

The following are just a few examples of how I like to use floral notes in perfumes that I consider very “masculine” in character.

Rose Geranium - the floral fruity rosy and herbal qualities make this

note perfect for masculine perfumes. It can be added for its sweetness as well as adding a herbal, slightly green aspect to the overall impression.

Orange Flower Absolute - Great for colognes and citruses of all types, but it can also be used for a more surprising, even a cutting edge oriental masculine fragrance - i.e.: using labdanum, vetiver, sandalwood, and spicy top notes for interest and depth. Orange blossom is also great as a heart note in tobacco based scents, to add a bit of indolic

sweetness, fruitiness and a sparkle to the dry leather notes.

Jasmine Grandiflorum - sweet and well rounded, this can be confidently used in masculine perfumes to bridge between sharp top notes and musky or mossy base notes. Try mixing it with lime, basil, lemongrass, lemon verbena, cloves absolute, tarragon, hay, oakmoss, vetiver, patchouli, fir absolute, and more. You’ll be surprised at how jasmine can transform these notes (and they definitely transform the jasmine too!).

Jasmine Sambac – this variety is more fruity and a tad more green (but in a very

delicate way) than the grandiflorum, Sambac is an interesting addition to a men's scent. Also great with tobacco, sandalwood, and green or herbal notes (i.e.: lemongrass, galbanum, rosemary, juniper)

Champaca - this spicy and heady tea-like and somewhat fruity exotic floral blends seamlessly into masculine compositions. Works great with spices, other fruity floral notes (geranium bourbon, rose, chamomile, etc.) and if you use a bold base with a definite statement, champaca will become masculine in an off-beat, daring way.

Rose – as I mentioned earlier, rose can be somewhat of a challenge for the Western perfumer, particularly if trying to use it as a main note. To overcome our prejudice of rose being feminine and soft, I learned how to mix roses with unusual bases and curious top notes to make it loosen up and reveal it's more aggressive side. For example: roses with cade and other leather notes will become a tough motorcyclist in leather jacket. Patchouli and Cocoa absolute darkens it as well... And than there is rose as a moderator of the composition - adding some sweetness and harmony to an otherwise unbalanced, harsh, sharp or overly spicy-medicinal presence.

Myth no. 3: “some notes are masculine, and some notes are feminine”.

Reality: As you’ve seen in the previous myth-crushing segment, context is everything. More than individual notes having specific gender, I would say the manner in which they interact with one another and the mood and personality they create is what truly matters. One thing that is true though, is that if thinking of the philosophical terms of what “masculine” and “feminine” mean, we could, perhaps, make the distYet, inction between notes that are “projective” as opposed to notes that are “receptive”. Notes that approach you as opposed to notes that draw you in. This might explain why notes such as citrus, herbs and spices are often considered more masculine and are used in abundance in masculine fragrances (they simply “come and get you”), while other notes – more round and “receptive” so to speak, such as the floral and ambery notes, can be more readily perceived as “feminine”. Still, don’t let yourself forget that what really matters is how all these notes interact with one another. The question you should ask yourself is if the perfume itself “projective” or “receptive”. If you are intrigued by this idea, I suggest you read the article by Octavian Sever Coifan:

The "Amber" Concept vs. The "Musk" Concept.

When you add a base of amber or oakmoss to citrus notes, you will get an oriental or chypre accords which both strikes me as a very feminine scents, reminiscent of a woman's own skin.

When you add herbs and citrus to a musky base of sandalwood, hay and ambrette for example, you will get a masculine citrusy - fresh perfume.

The same with flowers - add jasmine to hay, sandalwood and lemongrass, the result will not be all that flowery and "feminine".

Add jasmine to vanilla, labdanum and sweet orange, this will be quite soft and what we may refer to as "feminine".

To close this discussion, I would like to end with a few examples of breaking out the traditions of what “masculine” or “feminine” scents are.

A few years ago, I made a bespoke perfume for my friend Yasmin. Her name means Jasmine, and her house was always surrounded by Jasmine Grandiflorum in full bloom. She loves jasmine, but I didn't want to make the perfume too literal for her. Also, she doesn't like sweets very much. She loves sour citrus fruit and would eat half-lemons with their peels if she could, covered with salt rather than sugar! So I created a perfume for her composed of Jasmine Grandiflorum concrete at the heart, a head note of lime and ginger, and a base that has some vanilla sweetness tempered by the powdery bitterness of tonka bean and the astringency of frankincense. The result was quite an unusual jasmine scent. One that I would think men will actually love to wear too! My friend wore it for her wedding, and had to order a large refill for her signature scent shortly after.

On another note, a perfume that was planned to be "masculine" but ended up soft, complex and suitable for both men and women is a perfume called Rebellius - a melange of xantoxylum, champaca, cumin, tobacco, vetiver, rhododendron and juniper. Surprisingly, there were more women than men who bought this fragrance, and I am not under the impression that their femininity is in the least compromoised by doing so.

There were three occasions when the intense nonsense of gendered perfume hit me the hardest. One was when my friend Justin pulled up a sample of one of my Christmas scents I made in 2002 and told me how much he enjoyed it. To my surprise, it wasn’t “Fete d’Hiver pour Homme” (now known as Bois d’Hiver) – but rather, the gardenia and rose laden Fete d’Hiver. I smelled it on his skin and was in awe as to how masculine it smelled on his wrists. On another occasion, I was at a party wearing my perfume Tamya, and a man has insisted I let him try some on. I was surprised at his daring approach to a scent made up mostly of white flowers – jasmine, ylang ylang and a gardenia accord again. It smelled utterly delicious on him but did not make him smell any less masculine than wearing a tie. Than there was my own partner seducing me with his stolen spritzes of “L” from my elaborate perfume collection… I haven’t looked back on the matter of perfume gender ever since.