Jasmine: Fragrant Stars

Jasmine is as dewy as dawn itself, as sultry as a humid summer night. It's the first rays of sun through your bedroom window, and as dark as an insomniac's never-ending night. It's the sunny honeybee and at the same time a grey, dusty moth. Jasmine's elusive blossoms correspond to Luna, the moon, yet are able to create a solar energy within a dark, brooding perfume. Jasmine is associated with the sign of Cancer that is in rule most of July, and which is the only zodiac sign that is is ruled by the moon. And also, this is partly the time of the year when it is harvested for perfumery.

The complexity and emotional impact of jasmine are both beautifully portrayed in the following two poems, by Yusef Komunyakaa and Giovanni Pascoli:

Jasmine

by Yusef KomunyakaaI sit beside two women, kitty-corner

to the stage, as Elvin's sticks blur

the club into a blue fantasia.

I thought my body had forgotten the Deep

South, how I'd cross the street

if a woman like these two walked

towards me, as if a cat traversed

my path beneath the evening star.

Which one is wearing jasmine?

If my grandmothers saw me now

they'd say, Boy, the devil never sleeps.

My mind is lost among November

cotton flowers, a soft rain on my face

as Richard Davis plucks the fat notes

of chance on his upright

leaning into the future.

The blonde, the brunette--

which one is scented with jasmine?

I can hear Duke in the right hand

& Basic in the left

as the young piano player

nudges us into the past.

The trumpet's almost kissed

by enough pain. Give him a few more years,

a few more ghosts to embrace--Clifford's

shadow on the edge of the stage.

The sign says, No Talking.

Elvin's guardian angel lingers

at the top of the stairs,

counting each drop of sweat

paid in tribute. The blonde

has her eyes closed, & the brunette

is looking at me. Our bodies

sway to each riff, the jasmine

rising from a valley somewhere

in Egypt, a white moon

opening countless false mouths

of laughter. The midnight

gatherers are boys & girls

with the headlights of trucks

aimed at their backs, because

their small hands refuse to wound

the knowing scent hidden in each bloom.

- Poem via PoetHunter.com

Night Blooming Jasmine

by Giovanni PascoliAnd in the hour when blooms unfurl

thoughts of my loved ones come to me.

The moths of evening whirl

around the snowball tree.

Nothing now shouts or sings;

one house only whispers, then hushes.

Nestlings sleep beneath wings,

like eyes beneath their lashes.

From open calyces there flows

a ripe strawberry scent, in waves.

A lamp in the house glows.

Grasses are born on graves.

A late bee sighs, back from its tours

and no cell vacant any more.

The hen and her cheeping stars

cross their threshing floor.

All through the night the flowers flare,

scent flowing and catching the wind.

The lamp now climbs the stair,

shines from above, is dimmed...

It’s dawn: the petals, slightly worn,

close up again—each bud to brood,

in its soft, secret urn,

on some yet-nameless good.

- Poem via Poets.org

Botanical History

Jasmine is from the Oleaceae family and has originated either in either Persia, the Himalayan valley or India. Planting of jasmines (both official and sambac) were recorded as early as 3rd Century CE in China, and in the 9th Century, where it was indicated the plants came from Byzantium.But it was not until the 16th or 17th Century that it has found its way to Europe - with the Arab trade and Muslim concurs in the Middle Ages. It has been naturalized and cultivated in southern Europe as well as North Africa, and was adopted as an ornamental garden plant, where its scent can be enjoyed also in the evening after dark. Ecologically speaking, flowers like jasmine provide nectar and pollen for nocturnal insects such as moths. Their milky-white petals were also appreciated by other nocturnal creatures such as the Goth-inspirin ladies of Victorian times, who were eager to preserve their pale complexion and for them Moon Gardens were planted, with white night blooming flowers, among which was jasmine.

Traditional and Modern Extraction Methods

The Indians employed a "Sesame enfleurage"of sorts to obtain the fine perfume of jasmine. This was achieved by scattering jasmine blossoms among sesame seeds, in several batches. Once the seeds have absorbed the jasmine's fragrance, they would be pressed to produce a fragrant oil. Hot oil infusion of jasmine flowers - either J. grandiflorum or J. sambac - which then may or may not be blended into a sandalwood oil to produce the prized Attars - traditional Indian perfumes. The one from sambac is called Attar Motia; and the grandiflorum produces an Attar Chameli or Chambeli.

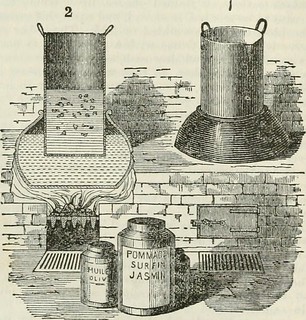

Enfleurage, one of the earlier modern methods (only about 250 years old) to obtain the scent of flowers that do not yield themselves to steam distillation such as jasmine, was developed in Grasse, France. With this extraction method, freshly picked flowers are arranged on trays onto which semi-solid fat is spread (usually of animal origin, with a mixture of tallow and lard achieving optimal results). This fat has to be as odourless and as insoluble in alcohol as possible. Flowers are left on these trays for extended periods of time to lend their fragrance to the fat; then, they are replaced with a new batch of flowers. It typically takes 36 batches of flowers for the desired result to be achieved before the pommade is ready for extraction. It is then washed by alcohol to produce an extrait, from which an absolute from pommade is the final result (used very much like other absolutes).

Most jasmines nowadays are produced by solvent extraction (using either hexane or previously, petroleum ether). That produces a concrete, which is treated with alcohol to separate the fragrant and precious absolute. Some of the jasmine odour stays behind within floral wax (a by-product of the solvent extraction), which is an interesting material to use in body products (body butters, soaps, etc.) and candles. I've seen references in literature to a "jasmine essential oil" that is produced from steam distillation of the absolute [4], but have never encountered it in real life, and have no idea what value such a product will hold - as many of the volatile materials in jasmine will be ruined in such high temperatures, making it a wasteful and costly raw material. I also can't see the value of this from a therapeutic standpoint - as the essence would have been already treated with synthetic solvents in the earlier stages of extraction. Traditional aromatherapists wouldn't be using either method because of their belief that trace amounts of the solvent are present in the finished product (which is highly unlikely).

Another interesting jasmine product is absolute from châssis: The exhausted flowers of enfleurage are called “châssis” (also the name of the trays in which the flowers and fat are arranged). These are further processed in hydrocarbon solvent to produce concrete from châssis, after they’ve been recovered from the solvent. Jasmine châssis is the most famous example of such a product that can still be obtained today. It provides an unusual scent, that is indole-free, and more reminiscent of orange blossom in its dark, fruity earthiness.

CO2 extraction of jasmine is also available, but only from the concrete. So again, we meet with a similar problem - it really poses no real value as far as the trace amount concerns (or any other issues with having synthetic solvents involved in the process of extraction). I've also found the finished products both inferior to the absolute with alcohol; and also just as expensive as the jasmine absolutes on the market - if not more. It is likely to include some of the floral waxes though, so that will give a more complete representation of the flower. However, floral waxes don't dissolve in alcohol so they will be filtered out in the process of perfume-making anyway, and will only hold value in oil-based products or cosmetic formulations such as lotions, creams and butters.

Alternatives to solvent extractions are currently being tested on small-scale, for example: vegan enfleurage, and using benign solvents to produce truly organic products from start to finish. I have sampled some of these products, but have found their quality to be inconsistent so far and the price far from competitive. Considering the high cost of jasmine absolute, this makes it very difficult to consider for commercial production, even on a small scale in an artisan fragrance house. These products are mostly valuable for personal use and in aromatherapy or other holistic, natural healing models.

Synonyms

Arabic, Persian, Hebrew: YasminChinese: Yeh-hsi-ming

Urdu: Motia (usually found in the form of Attar Motia - Jasmine sambac distilled into sandalwood oil)

Italian: Gelsomino

French: Jasmin (silent "n")

In English, it is also referred to as Jasmine, Jasmin, Jessamine, Poet's Jasmine and Common Jasmine.

In India, jasmine is referred to as "Queen of the Night", because its perfume intensifies after dark. Also, Motia is the name for the essence of J. sambac, and that from J. grandiflorum is called Chembali or Chemali.

Faux Jasmines

Other so-called "jasmines" that should not be confused with the real thing:1. Confederate Jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides), AKA Star Jasmine.

2. Poor Man's Jasmine (Ylang Ylang) neither looks nor smells remotely similar to jasmine, and deserves much more credit and admiration than just being a substitute for something it is not. If your nose has hard time discerning between the two - note that jasmine has significant amount of

3. Madagascar Jasmine (Stephanotis floribunda) is a tropical plant that despite its white flowers and heavenly scent, is not related to jasmine in any shape or form; but rather belongs to the Asclepiadaceae family.

4. Jasmine nightshade (Solanum jasminoides) is a plant I'm unfamiliar with, but judging by its name, is also fragrant and reminiscent of jasmine. There are other species with the same "surname", i.e. Gardenia jasminoides, which is also called "Cape Jasmine".

5. Gelsemium is also known as Carolina Jasmine

6. Jasmine rice is a type of long-grain, flavourful rice from Thailand, that owes its pandal-leaf-like aroma to 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, the same molecule that gives basmati rice its distinctive fragrant quality. It has a more subtle aroma than basmati rice though.

7. Brazillian Jasmine

8. New Zealand Jasmine (Parsonsia capsularis)

9. Red Jasmine is really a red frangipani (Plumeria rubra)

10. "Night Blooming Jasmine" really is Nyctanthes arbor-tristis and "Night-Flowering Jasmine" is the sweetly fragrance Cestrum nocturnum, which is also mis-named "Honeysuckle", at least in Hebrew (Ya'ara).

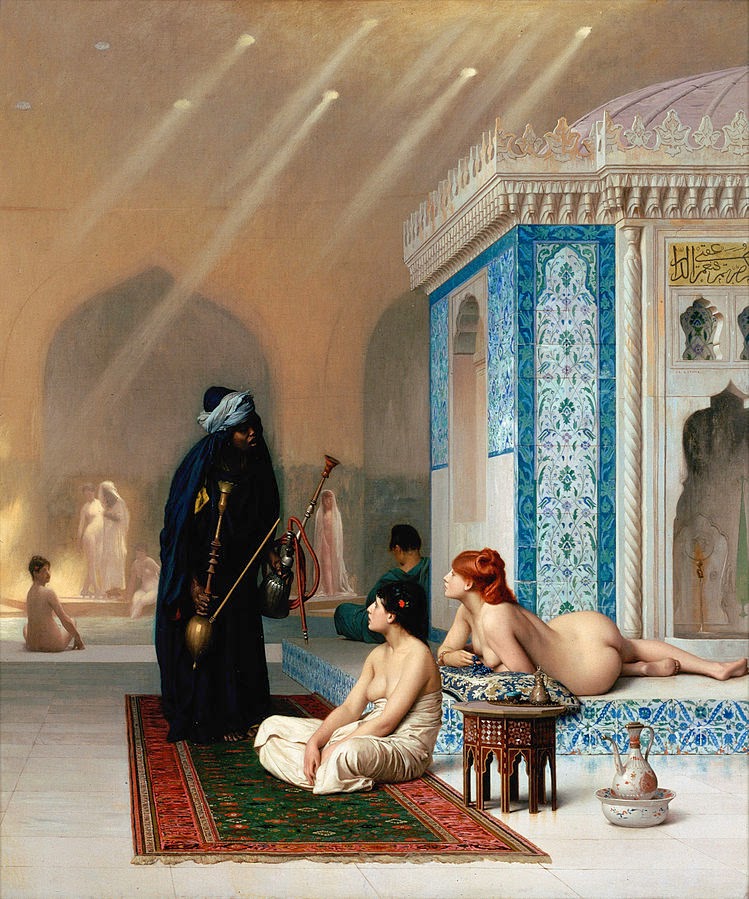

Cultural Significance of Jasmine

Jasmine is held in high regard the world over, and particularly in Asia and the Middle East. Kama, the Indian god of love, pierces people's heart with arrows that are topped with jasmine flowers. Sufi poets mention jasmine in their poems of longing for the divine and to express sensuality and love, for example: The Jasmine of the Fedeli d'Amore by Ruzbehan Baqli (a Persian sufi poet that lived from 1128–1209). [2]Jasmine sambac is the national flower of the Philippines and Indonesia; Jasmine officinale is the national flower of Pakistan, and the symbol of Damascus, Syria, which is also called "The City of Jasmine". Jasmine is a symbol of motherhood in Thailand, and is used as leis or necklaces during weddings in India and several other Southeast Asian cultures. Jasmine buds are stored on moist clothes in flower markets in India and are sold while still closed - only to be opened later at night when already adorning a woman's hair both visually and fragrantly. Jasmine flowers were used in China to decorate boat houses and in hair ornaments and bouquets for the (lunar) New Year's Day. [2]

Traditional and Medicinal Uses of Jasmine

In aromatherapy, jasmine is considered both a sedative and a stimulant, depending on how it is used and for whom. It is used to relieve headaches, and is considered to be both intoxicating, uplifting, warming and a tonic (therefore helpful in nervous exhaustion and fatigue). Western traditions associate it with the moon and the womb. It is used to assist women in childbirth and other issues with the womb (as it is considered to bring warmth to that organ), as well as for coughs, breathing challenges, cold and catarrh.In the emotional realm, jasmine's effect on the brain is fascinating: it releases encephalon - a neurotransmitter which has a mild analgesic effect. Hence, the smell of jasmine alone can bring a sense of happiness and euphoria, and reduce inhibitions and act as an aphrodisiac. [2] The Muslim doctor Al-Khindi entails in his book "Medical Formulary" a "Drug to excite intercourse: Throw in a good oil of jasmine and asafoetida and leave it for some days. Then the male organ is oiled with that oil of jasmine at the time of intercourse. The woman is excited by its contact and she experiences a strong lust". [2]

The Chinese used the J. grandiflorum flowers to treat hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and dysentery. J. sambac was used to treat conjunctivitis, dysentery, skin ulcers and tumours. Jasmine's root was used against headaches, insomnia, and to reduce pain from rheumatism or dislocated joints [4].

Beauty and Cosmetics

Jasmine's beneficial effects on the skin makes it a popular additive to skincare products, particularly facial creams where it can be enjoyed in small proportions - despite its costs. It is helpful for both dry, greasy and sensitive/irritated skin. Aside from its hefty price - the only downside for its use in creams is that due the indole causes them to get a brown discolouration. This can be avoided if using jasmine from châssis.Varieties of Jasmine

There are about 200 varieties of jasmine. The following summary focuses on those which are most fragrant and are in use in the fragrance and/or flavour industry.

Jasminum grandiflorum - a variety that is very similar to the J. officinale. Originates from East India, and the most commonly grown for perfumery uses. Unusually, their scent remains even after the flowers have dried - making them a good choice for tisanes and tea blends, as well as potpourri. Other names for it are Royal Jasmine, Catalonian Jasmine, Spanish Jasmine and Chambeli or Chameli (the Indian names for their attar, produced by hot oil infusion).

Jasminum officinale - with golden and silver-edged leaves, and the underneath of the flowers has a pink tint to it. It is used as the base for grafting J. grandiflorum in the South of France.

Jasminmum sambac (AKA Arabian Jasmine) - native to Arabia, and grows wild in India too. Some are single flowered, and some are double-flowered. Some varieties of J. Sambac also have multi-layered petals, similar to gardenia. Sambac jasmine is also called Sampaquita in the Philipines, Pikake in Hawaii, Tea Jasmine and Maid of Orleans.

Jasminum auriculatum, AKA Jasminum trifoliatum (AKA Tuscan Jasmine) - a variety of the Sambac jasmine that has three flowers.

Yellow varieties:

Jasminum nudiflorum (Winter jasmine) and Jasminum revolutum are fragrant yellow-flowered jasmines that original in China.

Jasminum odoratissimum is a Madeira (Portugal) variety but due to its quality of retaining its fragrance after drying, it is also grown in Formosa (Taiwan) where it is used to perfume tea. There have been successful attempts at extracting J. odoratissimum with solvent extraction, albeit with a low yield. The oil was analyzed and revealed to contain zero jasmone (the characteristic jasmine aroma), and the following constituents (compare to J. grandiflorum breakdown above):

6% Linalool

6% Linalyl acetate

1.6% Benzyl acetate

10% Indole and Methyl anthranilate

57% Diterpene or sesquiterpene alcohol

History and Significance of Grasse Jasmine

In 2009 I've visited the rose and jasmine fields at Mul, in Le Petit Champ de Dieu valley near Grasse. This are one of the very last few growers that still grow jasmine in the region. They have 3 hectares of Jasminum grandiflorum which are the home to about 60,000 jasmine shrubs. These fields are owned by the company of Chanel and are used exclusively for No. 5 parfum extrait. These fields were originally planted by monks who were faced by a common problems: shortage of pickers. This is especially true for the jasmine, since the pickers are paid based on how much they pick - where as in rose harvest, they are paid by the hour. The other problem is finding the market for the finished product. In the olden days, most of the homes in Grasse had little jasmine fields next to them, and they only had to pick the flowers, which they then brought to a cooperative extraction plant in the city for extracting the concrete and absolute (and before that, for enfleurage process). The cooperative took care of the marketing and sales of the finished products. Now most of the jasmine fields are gone because of land development (and the issues mentioned above - which most like has caused the former jasmine growers to sell their land).

Jasmine Harvest

The Jasmine harvest happens in the heat of the summer between August and September between 6-8 weeks, and takes place between 6am-2pm, with two weighings during the day to ensure quality. The jasmine that grows in the microclimate of Grasse produces a very fine aroma - it is far lower in indole, which is higher in Indian Jasmine.Jasmine Yield

As expected, the yield of jasmine oil varies depending on the the method used (i.e.: enfleurage or solvent extraction). You may be surprised to find out that the yield from enfleurage is much higher than from solvent extraction: 700 kg of flowers are required to produce 1 kg of absolute via solvent extraction; while only 250 kg were needed to make the same amount by enfleurage!Yet, in another strange turn of events - it is enfleurage that fell out of favour, while solvent extraction has taken over the majority of production of jasmine extracts.

How could this be so? The answer lays not only in quantity, but also in quality. The economic reasons of labour-intensive enfleurage are an obvious reason to switch to solvent-extraction. In addition, the quality of the absolute from enfleurage that is produced form flowers that have been macerating in animal fats for 24-48 hours or so is significantly quite different from the absolute. While the yield of enfleurage vs. solvent extraction stands at a ratio of 5:2 - we should not overlook the fact that the dying flowers change their aroma within that wide of a timeframe, and create a finished product with different characteristics and spectrum of odours.

What Does Jasmine Smell Like?

Jasmine is an exotic, narcotic and heady white floral note with luscious, fruity, tea-like characteristics. Generally speaking, "White Florals" are very complex, have many aspects because of the may molecules in their chemical makeup (over 100 in jasmine).Jasmine is particularly interesting because it is simultaneously intoxicating and fresh, heavy when smelled on its own yet shines light on a composition. This is true for jasmines, although it goes without saying that different jasmine varieties have distcintive odor characteristics (see more below). Likewise, different jasmine extractions highlight different qualities of the flower:

Jasmine grandiflorum absolute: Rich, opulent, special floral animalic notes (such as indole, skatole and paracresol). Floral, animalic, a little orange-flower like. It has a lovely, full-bodied fruity aspect that smoothes it out, giving it a creamy, delicious texture. The fruity note is somewhat reminiscent of white peach, but creamy rather than juicy. I have absolute from India, which is more earthy and indolic; and an absolute from Egypt which is lighter and smells like it has less indole and more hedione. This is how I would imagine the Grasse jasmine to be (although I have yet to encounter the absolute from this region).

Jasmine grandiflorum floral wax: Less indolic and of course less strong and complex than the absolute or concrete; but nevertheless holds a true jasmine scent that is unmistakable. My only complaint about this material is that its fragrance fades quite rapidly - so use it up within a year of purchase to prevent disappointments.

Less indolic and of course less strong and complex than the absolute or concrete; but nevertheless holds a true jasmine scent that is unmistakable. My only complaint about this material is that its fragrance fades quite rapidly - so use it up within a year of purchase to prevent disappointments.

Jasmine auriculatum absolute: The greenest of jasmine essences I've ever encountered. I am not at all fond of it, as I feel it is excessively grassy. There might be a problem with the particular specimen I have in my possession, but I can't comment as I haven't smelled others. I have used successfully in moderation to uplift green-floral compositions or to add to masculine fragrances, i.e. Gaucho.

Chemical makeup of jasmine:

Jasmine contains around 100 constituents, not of all have been identified, and many are present only in minute amount. A general idea of what jasmine absolute (from j. grandiflorum) roughly looks like this:65% Benzyl acetate

15.5% Linalool

7.5% Linalyl acetate

6% Benzyl alcohol

2.5% Indole (dirty, fecal, animalic, also present in civet – and feces)

3% Cis-Jasmone (the heart of a jasmine, unique to jasmine alone). Please note that there is also another isomeric form of jasmone - trans-jasmone, which is synthetic and usually will be present along synthetic cis-jasmone.

0.5% Methyl anthranilate (a Concord-grape-smelling component that gives jasmine its orange flower characteristic – also present in orange flower absolute, tuberose, ylang ylang and neroli)

Other components are present at trace amounts, of which the following were identified:

Paracresol (also an animalic component, almost leathery-smelling, present in narcissus)

Farnesol

Geraniol (hint of rosy/citrus)

Skatole (gives it a hint of earthy, dung-like smell)

Phenyl acetic acid

Methyl jasmonate

Methyl dihydrojasmonate (Hedione) - which smells floral yet light spacious, and is likely the main ingredient that gives jasmine its unique ability to make any composition feel lighter and more radiant.

Cinnamyl aldehyde (which lends jasmine its warmth and hint of spiciness)

Jasmine Compounding and Reconstitution

Jasmine can be reconstituted from synthetic materials, but the imitation leaves much to be desired.Generally speaking, cheaper raw materials are used to substitute for the authentic molecules that naturally occur in the absolute or enfleurage.

Benzyl acetate and and amyl cinnamic aldehyde (the latter at no more than 10% of the composition) provide a convincing imitation [4], and to that other elements which may sound surprising may be added to create a more realistic, natural and interesting jasmine base: maté absolute or tea absolute to bring forth the tea-like elements of jasmine; honey absolute to give it more rounded sweetness, tobacco-like raw materials such as chamomile or other "tobacco-leaf-like notes from ester of nicotinic acid (methyl or propyl)" [1] to give it a more believable character that is less flat or harsh. And of course - undecalactone (the "peach aldehyde") can be added to accentuate the fruity/juicy nuances, as well as ethyl methyl phenyl glycidate. Paracresols further enhance the animalic component of a jasmine base (reminiscent of narcissus); while civet, indole or skatole to add the animalic effect; and other floral notes such as ylang ylang, orange blossom absolute, tuberose absolute to round off and complete the methyl anrhanilate theme. One should use caution when using high levels of indole and methyl anthranilate - as they tend to develop a sour aroma over time that is quite unpleasant.

I have a couple of jasmine bases in my possession, both quite well-done - at least enough to fool me in my early days as a perfumer. One is a either a "nature identical" or a fragrance oil that was sold in health food stores in Israel. It's hard to say based on the labeling, and it is quite convincing so I used it before I knew any better. It has a bit of the tea-like quality, as well as a very pleasant fruity aspects of jasmine. It's not too indolic, but just enough to make it believable. I used it primarily to scent the room back in the day, and then in my early attempts at making high-class, resinous loose incense. It's when you burn it that it really gives away the fact that there is something synthetic in there.

The other is a vintage jasmine base that probably originated in one of the reputable European fragrance houses. It came my way as it was used to be sold at an antique jewellery shop, where the naïve owners believed these were vintage extractions or essential oils of labour-intensive flowers that were no longer in production. They had some exceptionally good bases there (even if labeled as essential oils) that they smelled quite believable for the most part, including narcissus, violet flowers, carnation, sweet pea, heliotrope and more. Of course I learned after a while what these are - and stopped using them in my perfumes altogether (I only used a handful of them anyway - ones I could not find anywhere else but thought they were possible to produce naturally, like the narcissus, orange blossom absolute, violet and carnation). Smelling them now is quite fascinating, because I have smelled many more essences every since and I can actually detect particular molecules within them (i.e.: heliotropine, ionones, anisaldehyde, paracresyl, etc.) In any case, this particular jasmine base was more animals, dense and heavy. I think I can detect more paracresol in there. It smells more like decaying jasmine flowers on an enfleurage tray, then the fresh dewy flowers in the (cheaper) nature-identical compound I found at the health-food store in Tel Aviv.

Jasmine's Role in Perfume

"There is no perfume without jasmine", the saying goes. And it is no exaggeration. In many compositions, it is thanks to jasmine that harmony and the feeling that something greater than the sum of its part was achieved.Composing with jasmine is a most satisfying, magical experience. It creates space when there was no room to breathe, it shines light on the darkest corners of a composition. The only other material which has a similar importance is rose - both having the ability to round-off a composition, smooth out rough edges, in other words what is called "bouquetting". But while rose can easily dense-up and clutter a composition (especially if it's already heading this direction) - jasmine has the talent of making any accord seem lighter, more put-tother, more pleasant, even if it wasn't quite so before it entered the beaker.

Jasmine is employed in all genres of perfumes. While its appearance is crucial in floral bouquets of the White Floral type and in Ambery Florals, AKA Florientals, it is also important as part of the bouquet of other Floral perfumes where it may play a less central role, contributing to the overall "floral" feel.

Jasmine makes more subtle appearances in the floral bouquets of any genre, including masculine fragrances:

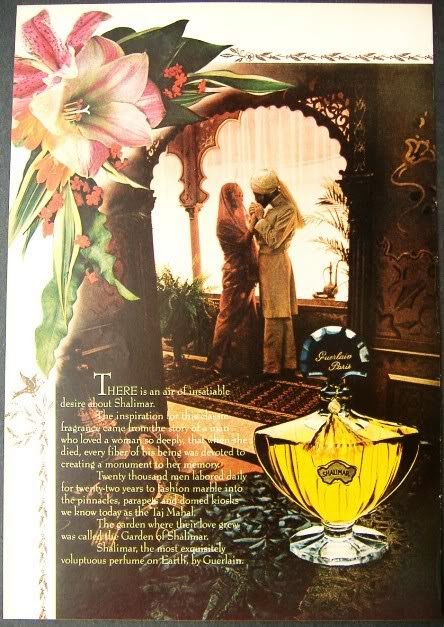

Oriental Ambery perfumes need jasmine like air to breathe. In the first perfume of that genre, Shalimar, the jasmine's fruity and sweet character helps to create a more smooth transition between the bergamot top notes and the syrupy sweet amber base (vanilla, labdanum, tonka bean, benzoin...) and creates not only a seamless ambreine accord but an entire symphony that plays fluidly from start to finish.

Oriental Spicy or Oriental Woody compositions require jasmine's lighthearted character to create a more spacious feel in what otherwise would have been a depressing pile of sawdust or heaps of medicinal-smelling spices. Even the tiniest amount of jasmine creates that feeling in such compositions, lifting up notes that could otherwise be overbearing, i.e. patchouli, cloves, etc. Opium is one excellent example, where the jasmine and mandarin oranges lighten up a dark melange of opoponax, myrrh, patchouli and eugenol-rich spices. Eau d'Hermes creates a similar juxtaposition with citrus and spice when it pairs jasmine with lemon and cumin to creates an original and timelessly off-beat masterpiece.

Chypre could never be the harmonious, cohesive, unified entity that we know from masterpieces such as Mitsouko, Femme, Miss Dior, No. 19, Crépe de Chine and countless others. Without jasmine, these masterpieces could have easily been a brown-mishmash of herbs and moss. It's jasmine, first and foremost that puts them in order and makes them smell like perfume.

Masculine fragrances such as the Fougère and Citrus Aromatic families benefit form jasmine's harmony-inducing qualities. Even the tiniest amount of pure jasmine absolutes adds its sunny presence, and brings out the best of otherwise contradicting elements. Case in point are Eau Sauvage, in which the methyl hydrojasmonate (Hedione) makes a staggering 40% of the composition, and making an otherwise dark and geriatric melange of moss, hay, basil and medicinal herbs smell happy and confident. Eau Sauvage's creative use of jasmine influenced countless other manly scents, including the iconic Azzaro. With its anisic and herbaceous character, it could have easily been a soapy, powdery Fougère like Canoe. However, the liberal use of citrus and the addition of a rather small amount of jasmine shines light on those elements and makes them look so much better than before.

Notable jasmine-y perfumes

The following list includes some fragrances in which jasmine plays a significant role, or at least is supposed to - but mostly perfumes that focus on jasmine as a theme (as a soliflore of sorts - some of which I don't necessary love or recommend). As it turns out, it is very difficult to find a remarkable soliflore jasmine, Companies are simply too cheap to use enough of the real thing to make it convincing, so sadly jasmine soliflores are in my opinion, leaving much more to be desired. Add to that the fact that I've grown up surrounded by the real flowers, and been fortunate to work with the best jasmine absolutes for the past 14 years - and you'll see why it's easy to disappoint me. I'd be curious to hear which jasmines are your favourites and continue my search for the perfect jasmine perfume!A La Nuit (Serge Lutens)

Alien (Thierry Mugler) - Jasmine sambac blown up by Helional

Arpége (Lanvin) - a succession of floral notes, jasmine being one of them

California Star Jasmine (Pacifica) - not even a star jasmine, and only barely-wearable

Diorissimo (Dior) - Breathtaking Lily of the Valley masterpiece by Edmond Roudnitska. Look for the vintage or better yet - the extract, where the jasmine absolute is quite evident, as are the green notes and boronia.

Donna Karan Essence: Jasmine (Donna Karan) - realistic jasmine

Drama Nuii (Parfumerie Generale) - fruity-lemony jasmine with musk

Eau d'Hermes (Hermes) - jasmine with lemon and cumin

Emotionnelle (Parfums DelRae) - Jasmine, violet and cantaloupe

Eau Sauvage (Christian Dior) - Hedione galore (a staggering 40%) in the heart of the father of all masculines. Masterpiece by Edmond Roudnitska, which means you must try it (look for vintage)

Éclat de Jasmin (Armani Privé) - soapy yet raspy jasmine-rose riding on a well-behaved fruitchouli and turning into Narciso Rodriguez shortly after

Fig (Aftelier) - jasmine and fir absolute

Honeysuckle & Jasmine (Jo Malone)

Ikat Jasmine (Aerin)

Jasmal (Creed) - jasmine and rose

Jasmin Full (Montale) - tropical jasmine candy

Jasmin de Nuit (The Different Company) - jasmine popsicle, with lemon and vanilla

Jasmin (Maître Parfumeur et Gantier) - Peachy jasmine

Jasmine AKA Clair-Obscur (Keiko Mecheri) - Soapy lily of the valley and jasmine

Jasmine (Madini) - jasmine fragrance oil, that is priced high and smells cheap

Jasmine (Scent Systems) - grassy-fresh jasmine

Jasmine Dawn & Dusk (Velvet & Sweetpea's Purrfumery) - herbaceous, indolic jasmine (botanical perfume)

Jasmine Pho - clear and transparent jasmine tea against fresh cilantro, basil and lime as they steep in a freshly brewed Vietnamese Pho noodle soup (botanical perfume).

Jasmine Tea (Artemisia Perfumes) - bejewelled jasmine green tea, with fir, osmanthus and green tea

Jasmine Rouge (Tom Ford) - realistically luxurious jasmine

Joy (Patou) - jasmine and rose

Le Parfum de Thérèse - jasmine, plum and basil sorbetto. Masterpiece by Edmond Roudnitska

Moon Breath - jasmine and incense (botanical perfume)

Opium (YSL) - jasmine, orange, patchouli and spices

Pink Jasmine (Fresh)

Poet's Jasmine (Ineke) - jasmine and tea

Private Collection Jasmine White Moss (Estee Lauder) - hedione and evernyl, rebranded

Sarrasins (Serge Lutens) - scary jasmine, or more accurately: a bucketful of indolic buckwheat honey.

Samsara (Guerlain) - jasmine and sandalwood

Sampaguita Jasmine (40 Notes)

Sampaquita (Ormonde Jayne) - modern Chypre with grassy jasmine

Sira des Indes (Patou) - jasmine banana

Songes (Annick Goutal) - jasmine ylang ylang heaven

White Jasmine & Mint (Jo Malone) - refreshing play on jasmine, with the addition of spearmint

Yasmin - jasmine soliflore (botanical perfume)

[1] Arctander, Steffen, “Perfume and Flavor materials of natural origin,” Allured Publishing, 1994

[2]Lawless, Julia "Aromatherapy and the Mind: The Psychological and Emotional Effects of Essential Oils", HarperCollins Canada/Thorsons, 1994

[3] Lawless, Julia "The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils: The Complete Guide to the Use of Aromatics in Aromatherapy, Herbalism, Health & Well-Being" Element Book Limited, 1992

[4] Poucher, W.a., “Perfumes, Cosmetics & Soaps with Speical reference to Synthetics Vol. 2 Being a treatise on the Production, manufacture and application of Perfumes of all types,” d. Van nostrand Company inc., 1959 (7th edition)