How do 4,000 years of uninterrupted use of sandalwood for religious, ritual, medicine and perfume end? Trust Western greed and corruption to take care of that... Since its introduction the Europeans in the 19th Century, Sandalwood's supplies have depleted significantly, and it is now an endangered species in its natural habitats; and the plantations of sandalwood world-wide can't seem to keep up with the demand.

Chandana (the tree's original name in Sankskrit) has a fragrant heartwood retains its scent for decades, which is what makes it so valuable. The trees have been cultivated in plantations in India for hundreds of years, where they've been used extensively for sacred carvings and temple gates, in daily religious rituals and in traditional

Indian perfumery (see below). It is only in the last hundred years or so there has developed large-scale interest in them in Western perfumery. The Indian government attempted to regulate the export of sandalwood, because India's demand for the wood only justified a very small amount (less than 10% of all harvest) outside of India. However, corruption among Indian officials, combined with Western greed, have pretty much exhausted the supply of East Indian sandalwood (

Santalum album). It is now considered to have a

vulnerable status by

IUCN.

What we are left with now, is a rapidly dwindling supply of

Santalum spicatum from Australia, New Caledonia and Vanuatu (the latter already made its exit from the market, probably until the next harvest - in 30 years or so, if anyone would remain patient and restrain their greed as to allow them to grow and fully mature and develop their fine aroma). In Australia, there are still some wild-harvested trees (and, as they tell us, felling of the trees is highly regulated and restricted as to protect the trees and allow them to reproduce).

Botanical Background:

Botanical Background:Sandalwood, the genus Santalum, are slow-growing

hemiparasitic trees that are native to India, China, Indonesia, The Philippines and

Timor, (

Santalum album), Australia,

Vanuatu, (

Santalum spicatum) New Caledonia (

Santalum austrocaledonicum) and Hawaii (

Santalum ellipticum,

S. freycinetianum, and

S. paniculatum). This evergreen tree reaches heights of up to 40ft, relying on neighboring plants for its survival - it leeches on to them underground and sucks their nutrients like a vampire. Sandalwood's essential oil exists only in its heartwood, which takes between 18-25 years to begin to develop; reaching its best quality and yield at 50-60 years of age. most trees are not given the opportunity to reach their optimal age, and this shows in the rapid decline in quality of the oils in the past 10 years alone.

Sandalwood thrives in the dry dedcuous forests of Southeast Asia and Australia and its surrounding archipelago. There are also several types of sandalwoods native to Hawaii (and probably already over-harvested). According to IUCN, the plant produces viable seeds at five years of age, which are distributed in the wild by bird. The threats to the species

Santalum album are "fire, grazing and most importantly exploitation of the wood for fine furniture and carving and also oil are threatening the species. Smuggling has assumed alarming proportions" (quoting from IUCN's website).

"Sandalwood trees freely produce seed and natural regeneration occurs both via seedlings and vegetatively via the roots. If left to mature, the trees can regenerate fairly quickly. The absence of heartwood in young trees provides little reason for felling trees less than 20-25 years old. However destruction of younger trees does occur and the age of trees that are now harvested has dramatically reduced. This is reflected by the quantities of oil in the wood. In the 1970s, 10 trees could provide 1 ton of sandalwood, but now more than 1000 trees are needed to produce 1 ton of wood". (

Kew.org)

Harvesting, Distillation and Extraction Methods:

Because the essential oil is concentrated entirely in the tree's heartwood, including the internal parts of the roots - it is necessary to fell the trees completely in order to make maximum use of the harvest. That is why sandalwood production, even more than with Agarwood (which might allow harvest without taking the whole tree down, by "tapping" into the trees) is so detrimental to the genus' survival.

Although trees only become fully mature and yield good quality oil beyond the age of 50, the age of harvest has rapidly declined to 30, 25, 20 and even 18 now... Resulting in far larger number of trees necessary for production of the same amount of oil that only required (see above). The reason I'm repeating this is because of how devastating it is to the trees, and because as a result, all the traditions, skills, arts and perfumes that rely on sandalwood, will disappear. It would soon be impossible to ever smell real mature sandalwood again, and is already extremely rare to come across a specimen!

The felling of younger trees to harvest their heartwood has greatly influenced the decline in sandalwood oil (and incense material) quality which I have witnessed within the past 12 years since I began working with this raw material. To say this is sad is an understatement. This is a tragedy in botanical, cultural and of course olfactory proportions (affecting both incense and perfume). Read on and you'll understand why...

The trees are often left outside the white ants (termites) to eat the bark (they do not like the heartwood because of the oil content), which saves a lot of labour. The heartwood is then sawed into billets, and sorted by the following "grades": Roots, billets, jajpokal, cheta and sawdust (Pucher, p. 366). The nicest and largest pieces will be used for carving and temple building, smallest pieces for distillation and for Japanese-style incense ceremonies, and the sawdust is used for incense making (the self-combustible type, i.e. joss sticks, incense sticks, cones and spirals). The distillation requires high-skilled workers that are experienced with this particular wood, not to mention all the preparation required (sawing, cutting, sorting, grinding). Large amounts of water, power and longer hours of distillation than many other harvests are contributing elements to the cost, in addition to the increasing scarcity of the raw material itself.

While most sandalwood is processed by steam distillation, solvent extraction products have been introduced to the market - sandalwood absolute and sandalwood CO2; both of which have a far poorer quality than the essential oil: lower odour intensity and tenacity, and not as fine aroma - probably because many other non-fragrant molecules have made it into the receiver. My conclusion is, that these extraction methods increase yield in weight and volume, but do not add favorably to the odour profile.

Religious and Spiritual Significance of Sandalwood:

Enter a Buddhist temple, and the first thing you'll notice is the soft smoke of sandalwood incense that wraps the atmosphere with serenity. Sandalwood is used throughout Asia in most religious practices, including Buddhist, Hindu, Shinto, Zoroastriansm and Islam. But it's religious and spiritual significance use is dated as far back as Ancient Egypt, where it is speculated to be one of the 16 ingredients recorded on a temple wall in the formula for the

Kyphi. The Israelites might have brought some with them from Egypt and have used it in the production of the Holy Incense burnt in the tabernacle, and perhaps also in the anointing oil for the temple's tools (the names in the holy scriptures are still rather obscure in regards to these aromatics' identities).

Hindu mythology has the sandalwood tree as surrounded by snakes; and the wood's long-lasting sweet fragrance symbolizes ineffable sweetness that is unchanged by danger. The perfume of sandalwood is believed to attract snakes, but the incense is burnt on a daily basis in Indian home to welcome the gods and ward-off evil spirits.

In both Shinto and Buddhist households in Japan, incense sticks (often made with sandalwood powder mixed with other spices, resins and woods such as sweet cassia, cloves, frankinences and oud) are burnt as an offering to the ancestors.

Sandalwood is considered to bring one closer to the divine in several religions, which is why it is used during funerals: In Hinduism, sandalwood logs were used in funeral pyres by the rich (not quite possible currently); In Islam, sandalwood paste would be applied to a Sufi's grave as sign of devotion by their students. In addition, burning sandalwood incense in memorial and funeral services soothes and comforts the mourners.

Muslim in India, and especially the south, would celebrate the holiday of Mohammed's birth (Milad un Nabi - literally translates to "birth of the prophet") by decorating images of Buraq, the mythical horse that took Mohhamed to Heaven, as well as the symbols of the prophet's foot-prints.

The Hindus apply sandalwood paste or essential to the "Third Eye" or the

6th Chakra Ajna, where it will elevate the spirit, increase spiritual awareness and awaken intelligence. Buddhists burn sandalwood incense in all their temples, to increase alertness and assist in meditation practices; as well as apply a special sandalwood paste called "Cathusama" (a mixture of sandalwood, agarwood, camphor, musk, saffron and other ingredients) to the Buddha icons and sculptures. Sandalwood-based incense powders are used to cleanse the monks and priests' hands before entering the temple.

According to Western alchemists, sandalwood has an affinity with the element of air, represents the cool lunar energies, and is most associated with the fixed air sign of Aquarius. It is also associated to a lesser extent with the planets Venus, the Major Arcana's Tartot card of The Empress. In Qabbalah, sandalwood incense will help connect one to the Sephirah of Netzah and the path of the letter "Daleth". In my early days working with alcehmical incense and perfumes, I've used sandalwood oil in

Moon Breath as a meditation and anointing oil, as well as in my

Zodiac perfumes for Gemini, Aquarius and Libra.

Traditional Sandalwood Carving:The close-grained nature of sandalwood's heartwood make it a very smooth wood, soft to carve and form many intricate designs in. Add to that its long lasting scent - and it is no surprise that many religious arts have formed around sandalwood, from creating meditation and prayer beads for malas, carving deities, and creating luxuriously-scented lace-like sandalwood fans that emit their delicate scent while fanning.

Medicinal, Therapeutic and Aromatherapeutic Properties:  Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurvedic medicine considers sandalwood to be a cooling, calming oil. Sandalwood powder is mixed with water into a paste to treat skin conditions that are associated with over-heating originated in "Pitta": sunburn, acne, rashes, herpes, infectious sores and also fever and ulcers. Mixed with coconut water, sandalwood was also prepared by ayurvedic doctors to further quench patients' thirst.

Chinese medicine uses sandalwood primarily for purification of the urinary tract. Western medicine acknowledged that role and for a while it was used in such way. However, these treatments were abandoned.

Santalol, the alcohols in sandalwood, are antiseptic which contributed to sandalwood's popularity in soaps. It also decreases skin inflammation, itchiness, etc. Mixed with honey and rice-water, sandalwood aided in treating digestive problems, and also was used in mouth-washing preparations to prevent bad-breath.

I have in my possession 3 sandalwood pills that are soft-gell covered and filled with an actual oil - a gift from Yuko Fukami. She told me that those were originally used to treat herpes (which is incurable, but the "cooling" effect of the oil ingested perhaps aided in reducing the symptoms). I cherish those not for their medicinal benefits, but because they are the only oil I have from properly aged trees!

Sandalwood is valued for protecting the skin from the sun. Some research is even beginning to find connection between sandalwood and treatment as well as prevention of skin cancer - so perhaps it's no coincidence on Mother Nature's behalf, that this tree still grows wild in Australia, the world's number one victim of that disease, as it sits right under the atmosphere's largest ozone hole.

Last but not least: sandalwood's healing effect on the mind is incredible - bring calmness and serenity and reducing depression, alleviating tension and anxiety. Therefore, it is not surprising that it's been used so widely in meditation, prayers and spiritual practices (see above).

Cosmetic Uses for Sandalwood:

Sandalwood not only smells good, but is also valued for its beautifying properties: acne-prone skin will benefit from the antiseptic qualities of sandalwood in a toner or cleaner it can balance the oils on the skin and stimulate healing; while dry and mature skin will improve regeneration and feel more soft and supple with the addition of sandalwood to creams, facial serums, etc. It is also used as in hair products such as hair oils. It is also used an all-natural sunscreen in Southeast Asia, similarly to how the girls in the above photograph have partially covered their face with its thin clay-like paste.

Aphrodisiac Qualities:Sandalwood's animalic and slightly uric qualities are no conicedence: this wood oil is surprisingly the

closest resemblence to the masculine pheromone

androstenol. It is therefore no surprise that in East Indian culture, jasmine and sandalwood are considered to be the most manly of scents.

Types and Aromatic Profiles of Sandalwood:

The most prized of all sandalwoods is the so-called "white" or "yellow" sandalwood (

Santalum album) that comes from plantations in Mysore, India. When the trees are allowed to fully mature, their aroma is so fine, beyond imagination: Precious wood. Creamy, woody, milky, warm, smooth, and very special. Most of the good stuff was gone just about ten years ago, and lesser quality stuff (from younger trees) replaced them, being only a poor representation of what this should be. The modern East Indian sandalwood oils have a certain acrid top-note, and dry down with a sour trail on my skin. This is not so with the original Mysore sandalwood, which once developed on the skin would convince you that your skin is made of silk and butter. It is milky, sweet, warm and rounded. Truly a gift from the Gods of perfume.

If you can find superior quality of East Indian sandalwood oil, it is most likely stashed away from before. And if it ain't, you should because it will in fact improve over time, giving way to more floral and sweet-warm characteristics to develop as the less pleasant bitter-woody notes dissipate.

Sandalwood Vanuatu is the only modern sandalwood oil that did not leave those sour, acrid skidmarks on my skin. It is different than the Indian one but to me that's a plus.

Australian Sandalwood (

Santalum spicatum): Floral, wood, warm, musky, sweet and smooth. Tenacious yet soft with incredible lasting power. Opens with sawdust overtones, and develops into a musky, warm, smooth, floral notes. Hint of nail-polish notes into the dry down. There is also an unmistakable urine-like note, which can be appealing - or not. It all depends on taste.

Ironically, sandalwood from Australia, which was considered such an inferior quality to the Indian (accounting still for about 90% of the world's production) and "posed no threat to it" (Arctander) is now the only viable alternative to the endangered

Santalum album.

It's important to note that some people have difficulty perceiving sandalwood. Similarly to ionones and certain musk - not everyone will get the depth and tenacity of sandalwood and might experience as a barely-there, almost transparent note.

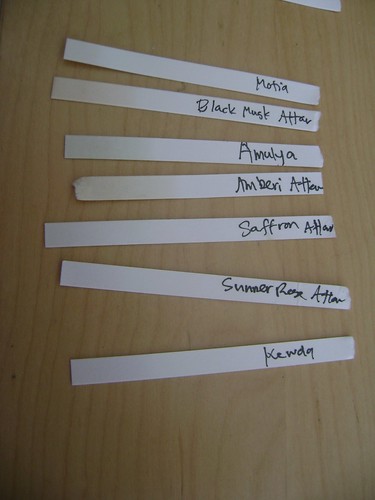

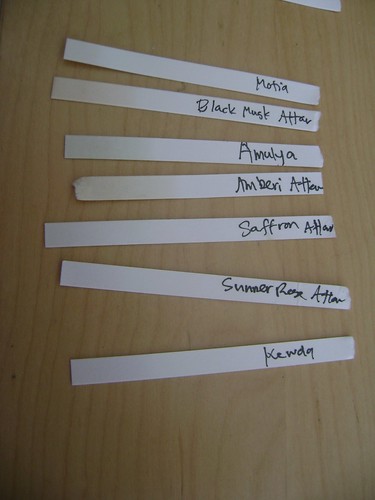

Role of Sandalwood in Attars - Traditional East Indian Perfumery:

Indian perfumery not only preceded Western perfumery and had immense technical advantage over it for hundreds if not thousands of years - it is also completely different from it, both technically and philosophically. And there is no better place to talk about Indian perfumery than within the context of sandalwood oil.

There is very little we know about the composition of traditional Indian perfumes, as the knowledge passes from father to son, from one generation to the next, orally and via hands-on experience of working together. Family's recipes are more than just trade secrets, as they were also protected by India's strict caste system. If you were not born to a perfumer's family, you can't and shan't be one. There was no way around it.

What we do know about East Indian perfumery is only from what we can smell - if we can get the real stuff; and from those who spent time with the distillers there. Equipped with a transportable copper still on his back, the Indian perfumer ventures into the wild to procure fresh aromatics - including getting all wet and dirty in search for waterlilies and lotus flowers inside ponds, and distilled into a receiver that contains pre-distilled sandalwood oil, which is by and large used as the carrier - you will find neither alcohol nor fatty oils in a true, traditional

Indian attar.

Dry materials, such as spices, resins and herbs are masterfully blended together, like a complex masala, prior to being distilled - either with sandalwood, or into sandalwood oil. The blending does not, in most cases, happen after the distillation, but beforehand. Beautifully complex perfumes such as Amberi, Shamama, Mukhallat, Majmuna, Kadam and many others are true complex perfumes with many secret ingredients, some of which are indigenous to India and mostly recognizable to the Western nose, with some ingredients more known such as rose, jasmines (there are at least three species available to the Indian perfumer!), marigold (tagetes), agarwood and more. And all of these, let's not forget, is suspended in a base of sandalwood oil!

Hence the importance of this raw material to the art of Indian perfumery. It is both aesthetically and technically impossible to preserve this unique, ancient art form that has been passed and perfected from one generation to the next - without the existence of this plant. While there are some creative attempts at finding alternatives - vetiver based attars, for instance - nothing would change the fact that we've been too greedy with our sandalwood consumption, we've over-harvested, and we still do not wait long enough for the trees to mature and develop their fine characteristics, not to mention replenish their own population.

Sandalwood in Western Perfumery:

Sandalwood oil has a distinctive precious-wood scent that is soft, warm, smooth, creamy and milky. It imparts a long-lasting woody base to perfumes from the oriental, woody, fougère and chypre families, as well as a fixative to floral and citrus fragrances. When used in smaller proportions in a

perfume, it acts as a

fixative, enhancing the longevity of other more volatile materials in the composition. Last but not least, sandalwood is a key ingredient in the "floriental" (aka floral-ambery) fragrance family - when combined with white florals such as jasmine, ylang ylang, gardenia, plumeria, orange blossom and tuberose etc.

Sandalwood easily gets along with all ingredients, and creates a precious wood note with a suave, soft, warm, velvety presence wherever it is placed. It goes particualrly well with rose, musk, ambergris, patchouli, cloves, cedarwood, cardamom, nutmeg, ginger, honey, ylang ylang, jasmine and all "white" florals. The main danger, however, is in burying sandalwood among very dominant notes where it would get completely lost rather than shine, so be cautious when you're marrying this costly essence with notes such as patchouli, oakmoss and the like.

A simple search for all perfumes containing "sandalwood note" on Basenotes yields a swooping number of over 3,000 results. Not all perfumes with that note truly contain the natural sandalwood oil; and even those who do - don't always have it in their forefront, including perfumes that have the word "Sandal", "Santal" or "Sandalwood" in their name.

Notable perfumes with a significant amount of sandalwood:

Bois des Îles,

Egoiste,

Samsara,

Tam Dao,

Santal de Mysore,

Cocoa Sandalwood,

Arpège,

No. 5,

Obsession,

Narcisse Noir and countless classical eaux (Crabtree & Evelyn, Floris, Yardley, Penhaligon) as well as modern niche houses (Lorenzo Villorsei, Etro, Amouage, Santa Maria Novella, Creed, Fresh, Tom Ford and many more).