Light in Perfume

Chanukah has flown by: a week-long celebration and opportunity for meditation on light. In recent years, I would have have been writing about olive oil or other kinds of oils to commemorate the holiday on SmellyBlog. This year I meant to talk about light the whole holiday, and am only getting around it now that it's just about gone.

The concept of light in perfume is an abstract and obscure one, which I find extremely fascinating yet not so much spoken of. You'll mostly see the word Light in perfume pertaining to weight, as in the French Légère, and not to any kind of illumination. There is a "Light" or "Lite" version of many fragrances, typically introduced for the summer months as limited editions. After screening out all these types of weightless fragrances, and perfumes with the word "Delight" in them, about a dozen surround the phrase "Moonlight", some relating to "Dawn", others to "Sunset" (including my own Sunset Beach), several to "Twilight" and ones pertaining to the very particular natural phenomenon of Northern Lights, Aurora Borealis - we are left with a few interesting names that actually include light in them as a concept. Among them stand out perfume names such as Bolt of Lightning (JAR), Twilight Shimmer (Michael Kors), Twilight Woods (Bath & Body Works), Light My Fire (Killian), The Night the Lights Went Out (Southern Comforts) Love's True Bluish Light (Ava Luxe) and Ray of Light (April Aromatics), as a few of the interesting ones name-wise. And then there is Moonshine, whose name perhaps originated from the state of mind created by methanol-laced homemade alcohol distillates, and in any case is only technically related to perfume via their shared medium, spirit.

When aldehydes first became popular with the, and were still considered "modern" (that was almost 100 years ago, when No. 5 by Chanel just came out), they were described as adding a "sparkle" to a perfume, which is a decidedly light-related word. It alluded to their abstract and modern quality, and an effect that was so new and different at the time. But it is really "sparkle" that they add, or is it diffusiveness? Is it a certain light-like quality, or it is more of a texture? Surely now there are other aroma chemicals that create a far more "sparkling" quality than those fatty, skin-like aldehydes ever did.

Otherwise, the concept of light is generally quite foreign to perfume jargon. Recent ad copies for perfume have been different though, often mentioning the obscure term "solar" to describe a range of quite different notes, from musk to amber to flowers. This trend began with Narciso Rodriguez For Her, touted as sporting a "solar musk note". Mind you, their much later fragrance NARCISO is far more sunny-smelling to me, but this time its theme is amber rather than musk. Very little explanation was provided at the time but the term stuck and can now be found in dozens of ad copies for millennial fragrances. I suppose in the same way we can say that sunflowers are "solar" in their shape, colour and behaviour - these notes add a quality of warm light, which is diffuse and soft - rather than the sharp and bright, broad-daylight sunniness of, say, an orange or a mandarin. When I think of analogues from my own natural palette, Roman chamomile essential oil comes to mind - a floral note that is warm, honeyed, fruity, sunny, yet soft and very diffuse. Using it definitely creates a solar energy so to speak in a perfume, and indeed, I have used this ingredient in both my Leo Zodiac Perfume Oil, and in the Sun Incense Pastilles. I am quite certain that nobody in the mainstream perfume industry thinks of chamomile, sunflowers or calendula when they are talking about "Solar Flowers" though. It is definitely something that is achieved by manmade synthetics, ones that I know next to nothing about.

The concept of light in perfume is an abstract and obscure one, which I find extremely fascinating yet not so much spoken of. You'll mostly see the word Light in perfume pertaining to weight, as in the French Légère, and not to any kind of illumination. There is a "Light" or "Lite" version of many fragrances, typically introduced for the summer months as limited editions. After screening out all these types of weightless fragrances, and perfumes with the word "Delight" in them, about a dozen surround the phrase "Moonlight", some relating to "Dawn", others to "Sunset" (including my own Sunset Beach), several to "Twilight" and ones pertaining to the very particular natural phenomenon of Northern Lights, Aurora Borealis - we are left with a few interesting names that actually include light in them as a concept. Among them stand out perfume names such as Bolt of Lightning (JAR), Twilight Shimmer (Michael Kors), Twilight Woods (Bath & Body Works), Light My Fire (Killian), The Night the Lights Went Out (Southern Comforts) Love's True Bluish Light (Ava Luxe) and Ray of Light (April Aromatics), as a few of the interesting ones name-wise. And then there is Moonshine, whose name perhaps originated from the state of mind created by methanol-laced homemade alcohol distillates, and in any case is only technically related to perfume via their shared medium, spirit.

When aldehydes first became popular with the, and were still considered "modern" (that was almost 100 years ago, when No. 5 by Chanel just came out), they were described as adding a "sparkle" to a perfume, which is a decidedly light-related word. It alluded to their abstract and modern quality, and an effect that was so new and different at the time. But it is really "sparkle" that they add, or is it diffusiveness? Is it a certain light-like quality, or it is more of a texture? Surely now there are other aroma chemicals that create a far more "sparkling" quality than those fatty, skin-like aldehydes ever did.

Otherwise, the concept of light is generally quite foreign to perfume jargon. Recent ad copies for perfume have been different though, often mentioning the obscure term "solar" to describe a range of quite different notes, from musk to amber to flowers. This trend began with Narciso Rodriguez For Her, touted as sporting a "solar musk note". Mind you, their much later fragrance NARCISO is far more sunny-smelling to me, but this time its theme is amber rather than musk. Very little explanation was provided at the time but the term stuck and can now be found in dozens of ad copies for millennial fragrances. I suppose in the same way we can say that sunflowers are "solar" in their shape, colour and behaviour - these notes add a quality of warm light, which is diffuse and soft - rather than the sharp and bright, broad-daylight sunniness of, say, an orange or a mandarin. When I think of analogues from my own natural palette, Roman chamomile essential oil comes to mind - a floral note that is warm, honeyed, fruity, sunny, yet soft and very diffuse. Using it definitely creates a solar energy so to speak in a perfume, and indeed, I have used this ingredient in both my Leo Zodiac Perfume Oil, and in the Sun Incense Pastilles. I am quite certain that nobody in the mainstream perfume industry thinks of chamomile, sunflowers or calendula when they are talking about "Solar Flowers" though. It is definitely something that is achieved by manmade synthetics, ones that I know next to nothing about.

The quest for very specific light-related terms has been occupying my mind for a few years now, since around the same time when I created Komorebi and learned of this unique Japanese term for the light filtering through the leaves, or more accurately, the interplay of light and foliage. Another interesting optical phenomenon pertaining to trees that garnered an English word of its own, is Sylvanshine: light retroreflected beams of lights (such as car headlights) from waxy leaves covered in dew-drops, which creates an illusion of snow in a midsummer night.

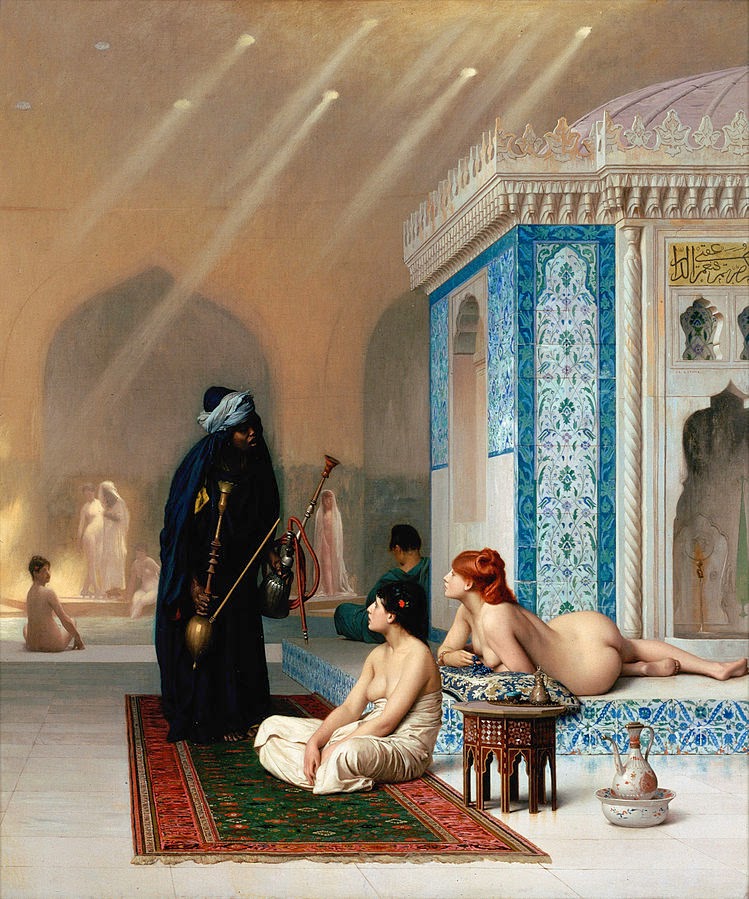

Foliage is not the only medium providing playing grounds for light. And light, although travels at a very constant speed, has many qualities in which it reveals itself. I've been in search for words to describe several light dispersing and other light-related phenomenon, and just in general, words that pertain to light, wether to describe it, qualify or quantify it. In this sense, writers are in much more luck than the film vocabulary designated to fragrance. We have words such as: Refraction, Illumination, Radiance, Brilliance... Light may Glow, Flash, Gleam, Sparkle, Twinkle, Dazzle, Glitter, Glisten, Glister, Glint, Glare, Flicker and may be Blinding, Bright or Dim. It may show up in columns, Shafts of Light, such as Beams or Rays; and in more technical terms, these rays may be Crepuscular or Anticrepuscular AKA Antisolar; or it may be Dappled such as the golden sunlight on the forest floor.

We have many light-words which are related to a time fo the day, beginning with the mundane and very useful "Day", "Night", "Morning" and "Afternoon". And since each of those happen daily - most people know what kind of light-quality is discussed, when light-related words such as dawn, sunrise, high-noon, sunset, twilight and dusk are mentioned. Similarly universal, yet perhaps less commonly discussed by lay-people are the Summer Solstice and the Winter Solstice, the Vernal Equinox and the Autumnal Equinox. Both have more to do with quantity of light (lengths of day and night). Other phenomenon may be relevant only to a particular part of the world, such as the Aurora Borealis is in the Arctic Circle; and the Midnight Sun in both poles.

Adjective pertaining to light may refer also to its colour as well, such as Iridescent or Opalescent and also pointing at its source of energy. For example - Fluorescent light which is transferred through gas, Phosphorescent, which emits the glow in delay, re-releasing light after its source has been turned off or removed; or Incandecant, which emits light though extreme heat, which happens when we overheat metal or glass, same thing that happens in old-fashioned light-bulbs. In essence, this is thermal energy (heat) which transforms into light energy.

We have many light-words which are related to a time fo the day, beginning with the mundane and very useful "Day", "Night", "Morning" and "Afternoon". And since each of those happen daily - most people know what kind of light-quality is discussed, when light-related words such as dawn, sunrise, high-noon, sunset, twilight and dusk are mentioned. Similarly universal, yet perhaps less commonly discussed by lay-people are the Summer Solstice and the Winter Solstice, the Vernal Equinox and the Autumnal Equinox. Both have more to do with quantity of light (lengths of day and night). Other phenomenon may be relevant only to a particular part of the world, such as the Aurora Borealis is in the Arctic Circle; and the Midnight Sun in both poles.

Adjective pertaining to light may refer also to its colour as well, such as Iridescent or Opalescent and also pointing at its source of energy. For example - Fluorescent light which is transferred through gas, Phosphorescent, which emits the glow in delay, re-releasing light after its source has been turned off or removed; or Incandecant, which emits light though extreme heat, which happens when we overheat metal or glass, same thing that happens in old-fashioned light-bulbs. In essence, this is thermal energy (heat) which transforms into light energy.

But I am looking for very particular and poetic descriptions of light! Light refracting in quiet water, creating myriads of coruscating, dancing veins, for instance. This phenomenon should have a name, but it doesn't as far as I know. The crepuscular light that shine down from the surface of the water when I swim westwards during the sunset time are nothing but awe-inspiring. It has a different mood and appearance than the rays of light you see at sunset dispersing to all directions from behind a cloud. Light simply behaves differently in water versus air. For those kinds of terms, we may turn to other languages, just as we did to Japanese for the term Komorebi. In Swedish, there is a word for the gleaming, road-like reflection of moonlight on the water: Mångata. Isn't it a fantastic word?

Back to the world of perfume: we do borrow vocabulary from other realms, such as light, to describe fragrances. So we may say a fragrance is radiant, iridescent, shimmering, luminous, sparkling, shiny, bright, light or dark. But which specific fragrances have those light-related qualities? Can we really relate to fragrances with such visual yet abstract terms without spilling over to the topic of synesthesia? How much is it marketing and associations, and how much is it that we really see and feel the colour purple when we small champaca; And is it really synesthesia or we just associated "chocolate" with "brown", "roses" with "red" and "smoky notes" with "black"?

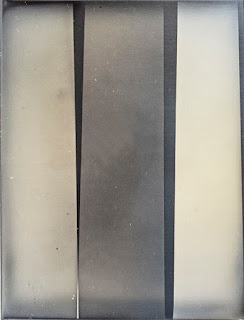

At the beginning of this year I have collaborated with a visual artist Sanaz Mazinanai, for her solo exhibit “Light Times” that explored the technical history of photography and its implication on this art form.when I created an ambient (environmental) fragrance named ILLUME for her art show dedicated to the history of photography. This was a conceptual art show, not truly a historical one, which explored the relationship of photography and memory, technology and the personal. Scent was not the only memory-related aspect of this abstract show. There was also music, composed by Mani Mazinani. The idea was how when we record something, for example through photographing it, as well as when we later associate a life event or a memory with scent or sound, its original meaning changes and perhaps even gets lost and is being replaced by these visual, fragrant or acoustic representations.

ILLUME sheds light on the concept through the sense of smell, which is subconsciously influential in our formation and retrieval of deeply rooted and emotionally charged memories. Being an environmental fragrance and part of an art show makes it public, perhaps even invasive, unlike the intimate and personal memories often elicited by perfume. Therefore, it was important to keep the scent simultaneously vague and familiar. It is immediately noticeable upon entering the space, yet not easily recognizable and identifiable.

Wherever there is light, there is also shadow. ILLUME explores this interplay of light with the shadows it casts, both in our collective memories and personal ones. The scent is agreeable yet abstract, with disturbing elements hidden in the background. Its design draws on chemical and technical themes such as minerals and acids, to create a reference to the dark room. These dominant acidic and mineral notes are light and sharp, but are only a mask to conceal the dark secrets and hidden memories - embodied with wet, mushroomy woods and smokey notes. Taken outside of their context, these familiar, mundane smells loose their meaning, or perhaps take on a new shape and identity.